Gabriella Kitch

Born and raised in San Diego, CA Gabriella has always had a strong connection to the environment and the ocean. She attended Washington and Lee, a small liberal arts school in Virginia for her undergraduate degree, where she discovered Geology. Captivated by the hands-on nature of the courses and the interdisciplinary science that challenged the way she viewed her surroundings and science in general, she ended up majoring in Geology with a minor in Environmental Studies.

Following her undergraduate studies, Gabriella moved to Chicago to attend Northwestern and join the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences for her PhD. In her free time she can usually be found with her nose in a book, doing yoga, eating or making delicious food, or snuggling with her golden retriever, Cora!

Welcome Gabriella! Can you share with us a little about your research?

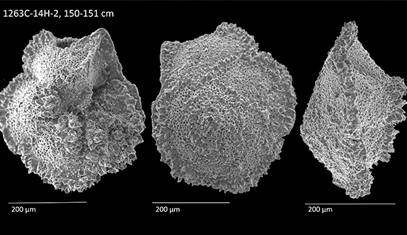

During my undergraduate degree I mainly focused on modern day water research questions such as water quality and mercury contamination. Through my undergraduate research experience, I was introduced to the world of geochemistry—as the name suggests this field uses chemistry toolset to answer geologic questions. I continued in this field for my graduate degree, but my geochemical research now has a paleoclimate focus, or a focus on climate change in the past. More specifically I work on identifying and constraining ocean acidification events in the geologic record. Ocean acidification is often referred to as “the other carbon dioxide (CO2) problem” or “global warming’s equally evil twin” because of how it impacts marine ecosystems. The ocean will absorb CO2 if concentrations increase in the atmosphere. When CO2 dissolves in the ocean it acts as an acid and this decrease in pH takes away the building blocks shelled organisms use to build their shells. This process is happening today, but ocean acidification events have also been identified in the geologic record where CO2 was released relatively quickly. Looking at how ecosystems respond to ocean acidification in the past may inform us about what is due to happen in the future. I use tiny fossil shells, called foraminifera, which are no bigger than a small crumb on a kitchen counter, to look at how the past oceans’ chemistry changed. Foraminifera are really great recorders of ocean chemistry because they build their shells directly from a little drop of seawater and therefore record environmental changes such as acidification and temperature changes. I have been in this specific line of research for four years and hope to continue for a lifetime!

What inspired you to be in your current field of study?

I think my introductory geology course got me hooked on the field since it really changed the way I viewed my surroundings. I suddenly had a means to tell a story, a history, about the environment I already loved. I was honestly intimidated by geochemistry, but became interested when I realized how accessible chemistry is once there is an application for the material. Chemistry holds such amazing tools to tell Earth’s history.

What are your aspirations for your research?

I am working with a newer tool in the field so I would really like to pursue major knowledge gaps in the field with that tool. My first goal is to write and defend my dissertation, then secure a postdoc using the tool I have focused on for my PhD! Once I wrap up with a postdoc, I would love to stay in academia or anywhere I can teach students about Geology!

What, in your opinion, are the biggest challenges facing climate research?

I think the biggest challenge in climate research today is bridging an interdisciplinary gap so that new policy reflects scientific knowledge. I think this issue is related to the push to effectively communicate climate research to students and the public that happened about a decade ago. I argue that rising to that challenge strengthened the field by increasing public support and interest, while also recruiting diverse approaches to research questions. I think we now need to face the challenge of communication between policymakers, economists, and scientists so that we can envision a sustainable future for society, the economy, and the environment.

What are some everyday things we can all do to positively impact our environment?

I think the greatest impact any one person can have is by simply talking about climate change with everyone in their personal bubble. For so long climate change has been politicized, but the science of climate change is now pretty readily accessible (check out resources on National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration's website for example). If we all discuss these facts with friends, family, and work colleagues we can really break down that political barrier and reframe discussions about the topic and the actions we can take to mitigate climate change. Individuals can also calculate (online) what the largest part of their carbon footprint is, and act to decrease those behaviors (i.e. meatless Mondays, choosing non-rush shipping, buying local, etc.). These individual actions also make great conversation points!

Do you think the current quarantine due to Covid-19 will have an impact on climate change? If so, how?

While some people have suggested that decreased pollution and carbon dioxide emission is a potential “silver lining” of world-wide quarantine, I think this is a dangerous conclusion to draw since our current living situation is not sustainable for society or the economy. However, I think that environmental resilience observations should highlight the effect humanity has on the environment and the ability we have to greatly reduce our impact. I hope that if COVID-19 has a lasting positive impact on climate change it will be due to realizations that we do not need as much as we have consumed in the past and we want to make a pledge to avoid another global catastrophe.

What would you like to tell those considering your field of research?

I think that everyone should take the time to learn about Geology! Understanding the Earth’s rich history provides a really unique perspective, especially in regard to human's impact on the environment. Continuing in the field is also very rewarding. It is so interdisciplinary that you can really tailor your research to your specific interests.